Apr 23, 2017 Kidnapped by Arnold Friend she must try to survive and escape from his grasps. A character originally based around serial killer Charles Schmid. We take on the aspect of human trafficking.

Character Analysis

Signs that a guy might be trouble:

- The first words out of his mouth are 'Gonna get you, baby.'

- He stuffs his boots so that he looks taller, even though it makes him walk like a drunken pirate.

- He has a picture of himself spray-painted on the side of his car, a picture that makes him look like a 'pumpkin.' (Pumpkin + smile = jack-o'-lantern.)

- He seems to be around thirty (maybe even old enough to be your father), but he tries to look like a teenager.

- You'd pity him for trying so hard, except that he's also threatening to abduct you.

- He admits to stalking you and finding out all kinds of details about you from your so-called friends.

- His idea of flirty banter is threatening your family with bodily harm.

Ah, if only Connie spent less time listening to the radio and more time reading Shmoop. (Couldn't pass up an opportunity for shameless self-promotion.)

As Connie tries to get a handle on Arnold, she realizes that:

She recognized most things about him [...] even that slippery friendly smile of his, that sleepy dreamy smile that all the boys used to get across ideas they didn't want to put into words. [...] But all these things did not come together. (77)

Arnold is a 'blur,' and every attempt to see him for what he really is only generates 'dizziness' rather than mental clarity (94).

That's because Arnold Friend is a blend of some familiar types from literature and pop culture. He's the Matthew McConaughey character from Dazed and Confused, the guy who still hangs out at high school way after he's graduated. But he's also got qualities that a long literary tradition associates with evil – like Milton's Satan in Paradise Lost or Dostoevsky's devil in The Brothers Karamazov. (Want more devilish connotations? Take out the 'r's' from 'Arnold Friend' and you're left with 'An old fiend.')

Like these great literary bad guys, Arnold can zero in on the weaknesses and desires of those around him – in this case, Connie's romantic fantasies. And like these incarnations of evil, Arnold's greatest tool of manipulation is a forked tongue. He's a travesty of morality, the 'Friend' who isn't a friend. He keeps his promises, but his promises are all threats. Coming from his lips, the word 'love' loses all of its idealistic connotations and becomes a violent and obscene thing.

No matter what Connie says or does, Arnold keeps talking – and yet he reveals nothing about himself. He never physically coerces Connie to join him, but his words have the same force and pull as the actions he only threatens to take:

'Soon as you touch the phone I don't need to keep my promise and can come inside [...] anybody can break through a screen door and glass and wood and iron or anything else if he needs to, anybody at all, and specially Arnold Friend.' (116-118)

Death or evil incarnate posing as an ordinary man: this is the mess of contradictions that makes Arnold Friend so terrifying and so unforgettable.

The Man without Identity: The Multi-Faceted Arnold FriendThe character Arnold Friend in Joyce Carol Oates’s short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” presents to literary critics and readers alike the seemingly unanswerable question of who or what he is or represents. Joyce M. Wegs asserts that Oates “makes no […] effort to explain the existence of Arnold” (617). In fact, Oates herself seems to have trouble defining Arnold Friend, claiming he is based on serial killer Charles Schmid to “musical messiah” Bob Dylan and every other applicable personage or role that is suggested to her (Schulz and Rockwood 595; Tierce and Crafton 609). The task of suggesting the possible identities has fallen to her critics and to her readers.

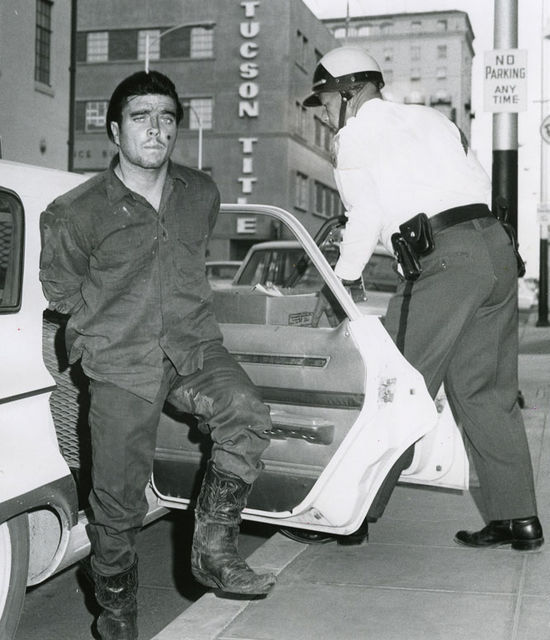

One of two most widely accepted critical theories is that Arnold is a rapist and murderer. Of Friend, Wegs says, “[H]e is not simply crazy, but a criminal with plans to rape and probably murder Connie” (616). If Arnold Friend is such a criminal, the critics can then parallel him to Charles Schmid, the “Pied Piper of Tucson,” a twenty-three-year-old who had gained his fame the year before the story was first published (Schulz and Rockwood 595). Schmid found his victims by dressing as the teenagers, “cruis[ing] in a golden car [and] haunting ‘all the teenage hangouts’” (Schulz and Rockwood 595). Oates’s Arnold Friend dressed “the way all of them dressed” and first meets Connie at the “drive-in restaurant where […] kids hung out,” and just like Schmid, in a gold-painted car (Oates 584; 580).

Connie is also constantly having the title of “victim” conferred on her by the critics, “X for victim” (Wegs 617); “Arnold’s young victim” (Schulz and Rockwood 596). This only relates Schmid and Friend more closely. The sudden end of the story subtly leads most readers and critics to believe that Connie will meet her death at the hands of Arnold Friend, as did Schmid’s young victims.

“However, Arnold Friend is far more than a grotesque portrait of a psychopathic killer masquerading as a teenager; he also has all the traditional sinister traits of that arch-deceiver and source of grotesque terror, the devil,” declares Wegs (616). Arnold Friend’s equation with the devil is the other of the two most widely accepted theories as to his true identity. Of all critics, Wegs is the most blunt, stating simply that “Arnold is clearly a symbolic Satan” (617). Arnold Friend’s similarities to the demon-king fall into his appearance, mannerisms, and even extend into his name.

Satan is traditionally portrayed as short, just as Schmid and Friend. Both Schmid and Friend pack their boots to add height so as to appear taller, giving them a faltering, “awkward, stumbling walk” which could also be attributed to Satan’s “cloven feet” (Schulz and Rockwood 595; Wegs 617). The traditional demon also cannot “cross a threshold uninvited” which may very well be the reason Friend does not go into Connie’s house (Wegs 617). Wegs points out that his last name of “‘[F]riend’ is uncomfortably close to ‘fiend’” and that “his initials could well stand for Arch Fiend” (617).

Arnold also tells Connie that he will “come inside [her] where it’s all secret and [she]’ll give into [him]” (Oates 587). Instead of the sexual connotation that Schulz and Rockwood bring to light, perhaps he means that he will go into her heart and soul through his demonic powers and break her to his will.

In Greek mythology, Hades is the same as Christianity’s Satan. If Arnold is Satan, he could also be called Hades, which brings yet more similarities. Hades came up from the Underworld (Hell) and abducted Persephone, daughter of Demeter. If Arnold is Hades, then Connie becomes Persephone. The similarities between Connie and Persephone do not end with their abduction and possible rape by men of the Underworld. Both young virgins cry out for their mothers to save them. They each are very beautiful and have long hair, said to add to their beauty. Both Connie and Persephone are taken in an open vehicle, Persephone in a chariot and Connie in Arnold’s “convertible jalopy painted gold” (Oates 581). Wegs asks if Arnold’s car could be “a parodied golden chariot,” not unlike the chariot of Hades would be (616). Most certainly Connie’s parents, specifically her mother, would go looking for their missing daughter, just as Demeter searched the earth for Persephone. Though Connie’s disappearance into the Underworld will surely not result in four seasons, but will certainly cause family and close friends great pain.

If Arnold and Connie are Hades and Persephone of Greek mythology and present-day society looks at Greek mythology as an ancient religion, as well as folk tales or fairy tales, then Arnold and Connie can be equated to the many charachters of our ages-old fairy tales. Many “fiends” of popular fairy tales have demonic influences in their character, just as has been established in Arnold Friend. The many wolves of common fairy tales are found in “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”

Arnold’s clumsy gait could be attributed to a tetrapod (four-footed, as in a wolf) acting as a bipedal human (Schulz and Rockwood 602). Little Red Riding Hood notices her wolf’s big teeth, as does Connie. Arnold’s teeth are “big and white” which adds to his wolfish appearance with “shaggy black hair” (Oates 586; 581). Also indicative of Arnold’s lupine side is his act of “sniffing as if [Connie] were a treat he was going to gobble up” (Oates 584). Another Big Bad Wolf of the fairytales is the one that plagued the Three Little Pigs (Schulz and Rockwood 603). Just as the original wolf threatened to destroy the houses of the pigs, Arnold Friend coincidentally threatens to tear down Connie’s house (Schulz and Rockwood 603).

Beauty’s beast-prince only returned to a handsome prince once she loved him for who he was on the inside and not what he looked like. Arnold could well be Connie’s beast-prince that will only return to his real form from his beastly appearance once she “learn[s] to love him for himself” (Schulz and Rockwood 603).

Arnold could also be Connie’s average fairy tale prince, come to save her from the life she is living, not unlike the princes of Cinderella, Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and Rapunzel (Schulz and Rockwood, 600-01). This transformation then leads to another, changing Arnold from demon to saint and savior. As Roy Male explains, “[M]any mysterious intruders throughout American literature ‘are almost always potential saviors, destroyers, or ambiguous combinations of both’” (qtd. in Tierce and Crafton 608).

Tierce and Crafton say Arnold’s “arrival could be that of a savior” (608). Arnold states time and again in the story that Connie’s family “don’t know one thing about [her] and never did” (Oates 591). Moreover, Tierce and Crafton argue that “[Bob] Dylan provides a physical model for Arnold’s appearance” and call Dylan a “musical messiah” (609). Arnold Friend shares Bob Dylan’s characteristic messy black hair, long nose, thick eyelashes, short stature, and face of stubble (Tierce and Crafton 609). Also noticeably Dylan’s is Arnold’s voice, a “fast, bright monotone” (Oates 583).

“Bob Dylan’s followers perceived him to be […] ‘Christ revisited’ [and] a type of rock and roll messiah,” say Tierce and Crafton (609). Tierce and Crafton also believe that Dylan and Friend are one in the same and call him “the troubadour, the artist, […] the actor, the rhetorician, [and] the teacher” (608).

Looking at Arnold as a teacher, he can then become a character of Plato’s “underground cave,” which “illustrates people’s predisposition to accept things as they find then and resist change,” just as Connie resists the change that Arnold presents to her (Rouse 26). Much like Schulz and Rockwood’s womb, Plato’s cave is where Connie retreats, hoping to find safety form Arnold and the change he represents (605). Also similar are Schulz and Rockwood’s fairy tale Woodcutter who coaxes Connie out of her second womb without the physical force of the model Woodcutter and Plato’s attendant who drags the unfettered prisoner from the cave, who, as Arnold Friend, simply coaxes out of the relative comfort of the cave (605; Rouse 27).

Connie finally embraces and accepts the change that Arnold Friend brings and leaves behind the safety of her father’s house, her cave, and steps out to stare in wonder at a reality outside of her cave that Arnold has coaxed her into (Rouse 27-28). When she finally leaves her father’s house, he second womb, her cave, she sees “the vast sunlit reaches of the land […] so much land that Connie had not seen before and did not recognize except to know that she was going to it” (Oates 519).

This great change brings with it great fear in Connie. A reader only meets Arnold as Connie does, and he is thus cast in a light of terror and sorrow. This resulting appearance leads readers and critics alike to view Arnold as a psychopathic, demonic rapist and murderer.

From reading the critical theories, a reader becomes more intrigued as to the identity of the mysterious Arnold Friend, just as Connie who “becomes more concerned about knowing his real identity” and where he has come from does (Wegs 618). Each theory is just as valid as its predecessors and successors and deserves just as much recognition. The old cliché, “To each his [or her] own,” surely holds true as to discovering the identity of Arnold Friend: demon, saint, teacher, messiah, fairy tale prince, Bob Dylan, and so much more.

.

Works Cited

Oates, Joyce Carol. “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. 3rd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1997. 597-91.

Arnold Friend Based Serial Killer Killer

Rouse, John Clive Graves. “Living in a Cave.” Trans. W. H. D. Rouse. The Great Dialogues of Plato. Ed. Eric H. Warmington and Philip G. Rouse. New York: New American Library, 1956. 26-28.

Schulz, Gretchen, and R. J. R. Rockwood. “In Fairyland without a Map: Connie’s Exploration Inward in Joyce Carol Oates’ ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. 3rd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1997. 595-607.

Serial Killer Fbi Based Serial Killer Profile

Tierce, Mike, and John Michael Crafton. “Connie’s Tambourine Man: A New Reading of Arnold Friend.” Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. 3rd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1997. 607-13.

Wegs, Joyce M. “‘Don’t You Know Who I Am?’ The Grotesque in Oates’s ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?’” Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. 3rd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1997. 614-19.

back